Sam Altman vs. Miss Manners

Why “please” and “thank you” aren’t the waste you’ve been led to believe

Most readers won’t recognize the name, but for a while, Miss Manners was a household name. Her real name is Judith Martin. She started her column in 1978 writing for the Washington Post. She’s a cultural journalist focused on etiquette. One of her many books was titled, Miss Manners Guide to Excruciatingly Correct Behavior (1982). She still writes today but her work isn’t as relevant to modern culture as it once was, which is too bad. Miss Manners philosophy is that etiquette isn’t about snobbery. It’s about kindness and respect - making people feel comfortable.

Fast Forward to April 2025. You likely saw a rash of articles talking about how ChatGPT CEO Sam Altman “admitted” how saying things like “please” and “thank you” to ChatGPT wastes tens of millions of dollars.

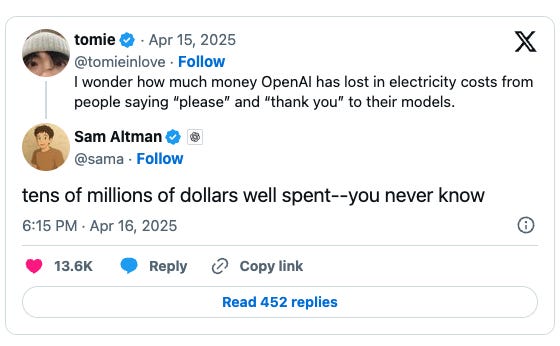

It’s important to first set the record straight. This is not what he said. It’s no surprise the Internet decided to twist the actual conversation to gin up some controversy (something Miss Manners frowns upon). The actual exchange was as follows:

@tomieinlove: “I wonder how much money OpenAI has lost in electricity costs from people saying please’ and ‘thank you’ to their models.”

@sama: tens of millions of dollars well spent--you never know

Altman’s typically a pretty straight forward person so it’s hard to read exactly what he was trying to say here other than a back of the envelope calculation along with a possible mention that it might have actually been money well spent. Like he said, you never know.

ChatGPT functions through what is called Natural Language Processing. This is a concept that gets lost when talking about how we interface with Large Language Models. They are essentially pattern recognition mechanisms. So the idea that some parts of our language are wasteful while other parts are not is really a misguided concept rooted more in theoretical engineering efficiency than in real knowledge of how these systems work. How you interact with them teaches them as much about you as anything and teaches them generally what to expect when dealing with people as a whole.

It’s important to note that these two terms represent a tiny sliver of actual text generation.

Based on data from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA), the words "please" and "thank you" each occur approximately 1,000 times per 100 million words, equating to about 0.001% frequency individually. Combined, they represent roughly 0.002% of the corpus. This suggests that, on average, one of these words appears once every 50,000 words in written American English.

Yet these incredibly infrequent interactions have real meaning. In natural language processing (NLP), polite salutations like "please" and "thank you" mainly serve three subtle but important roles:

Intent Softening:

They make requests seem less demanding.

Example: "Please send me the report" vs. "Send me the report."

NLP models must learn that both mean the same action is requested, but one is more socially acceptable.

Sentiment Shaping:

They raise the emotional tone of communication, signaling friendliness, respect, or gratitude.

Sentiment analysis models use words like "please" and "thank you" to detect positive sentiment.

Disambiguation Cue:

Sometimes, politeness helps models infer meaning and intent.

If a phrase includes "please," it's probably a request, not just a statement.

More importantly, they beg the question - why exclude one set of words while letting others remain? That feels really arbitrary. If the intent is to reduce cost, why not just revisit the concept of language generally? Natural Language Processing is about building a very human bridge to our machine counterparts. English is wildly inefficient as a machine interface system - not the least because it is deeply abstract and riddled with contradictions. The logic strain of trying to understand context, colloquialism and other human factors will likely be exponentially more energy hungry than a simple salutation or note of appreciation.

Noted psychologist and AI expert Gary Marcus talks about this in his book Kluge when he mentions how we, as humans, don’t drive on driveways or park on parkways. More to the point he says,

“Language builds on our cognitive capacities to reason about the goals and intentions of other people, on our desire to imitate, our desire to communicate, and our twin capacities for using convention to name things and sequence to indicate differences between differing possibilities.”

This underscores how the point is not saving electricity. Cutting linguistic corners will have no impact on the fact Large Language Models are inherently power hungry systems. It does beg the question though of what we’re even trying to do here. We are trying to teach machines who we are as humans. If that’s not the case then there are dozens of more efficient means of communicating. These machines would likely consume substantially less power if we just spoke to them in code or in hexadecimal.

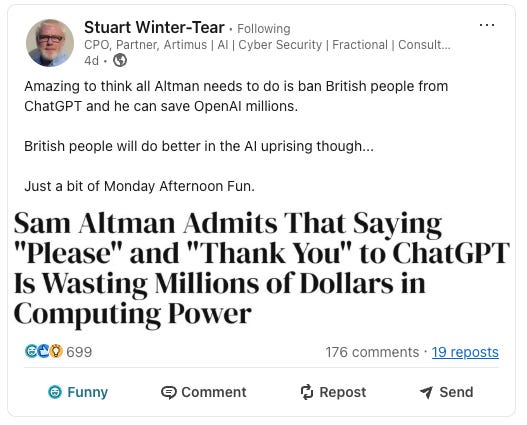

Noted AI expert Stuart Winter-Tear makes light of this when he says, “Amazing to think all Altman needs to do is ban British people from ChatGPT and he can save OpenAI millions.”

All kidding aside, the point is not to pinch pennies but to engineer a system that effectively merges natural human tendencies and interactions to Artificial Intelligence capabilities. Curating our natural behaviors will only reduce that effort. And it will distract from the myriad of problems, not the least of which is we still have no clue what happens inside the system once we decide whether to say please or not.

Getting back to Miss Manners - the point of being polite (etiquette) isn’t to be a snob. It’s to show respect. But how will machines ever know that if we’re so focused on cutting out 1 in every 50,000 words because we think it will solve our energy problems?